Tuberculosis

Control of tuberculosis (TB, sometimes called ‘consumption’) became an issue in Victoria from the 19th century and Dr Dan Gresswell was responsible for much of the initial policy, procedures and medical treatments. Treatment involved quarantining patients and ensuring better sanitary conditions for the population generally. https://www.montparktospringthorpe.com/721-2/

Government–run sanatoria were set up at places like Greenvale and on the Mont Park Hospital site. These were on tracts of Crown Land and some parts of these areas remain as natural bushy Reserves to this day.

By the 1950s and 1960s TB infection was being successfully controlled by new drugs, and the spread of TB and other contagious diseases like diphtheria, scarlet fever, measles, whooping cough, meningitis and polio were being contained. See https://www.montparktospringthorpe.com/gresswell-and-tuberculosis/

WWI and TB

Many soldiers returning from the early years of WWI had contracted TB in the trenches of Europe, and came back in very poor health.

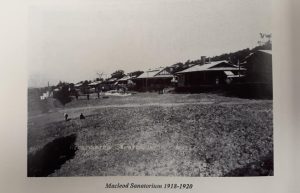

The No. 1 Military Sanatorium Macleod was opened in 1916 to provide care for military veterans with tuberculosis, catering exclusively for soldiers, see https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/155086241

It was located on the eastern slope of Gresswell Hill in the Mont Park hospitals complex.

Other private TB Hospitals were available for civilian patients, including the large Gresswell Sanatorium/Sanatarium which opened in 1933 on the north-east slope of Gresswell Hill. See https://www.montparktospringthorpe.com/gresswell-and-tuberculosis/

The Gresswell Hill site for Macleod and Gresswell Sanatoria was chosen as it was isolated, yet part of the Mont Park Mental Hospitals precinct. The hospitals could share resources including medical and service staff. Furthermore there were Melbourne suburbs close enough to ensure people could be recruited to work at the Sanatoria. Less medical staff were needed in a Sanatorium ward than in Mont Park asylum wards, because the TB patients were mobile and capable of helping with the cleaning and meals, and were not receiving any medications.

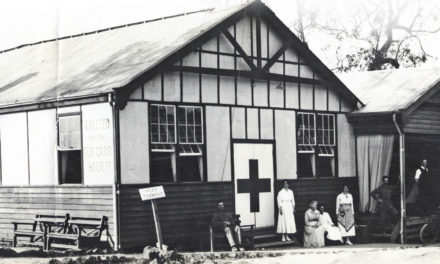

Since it was a Sanatorium, patients were to be exposed to fresh air and sunlight to aid their recovery, and could do light work. Visitors came via the railway to Macleod or Watsonia stations which were about a mile away (1500 m). Families also came from Heidelberg station. The Red Cross generously provided cars to pick up visitors from the stations.

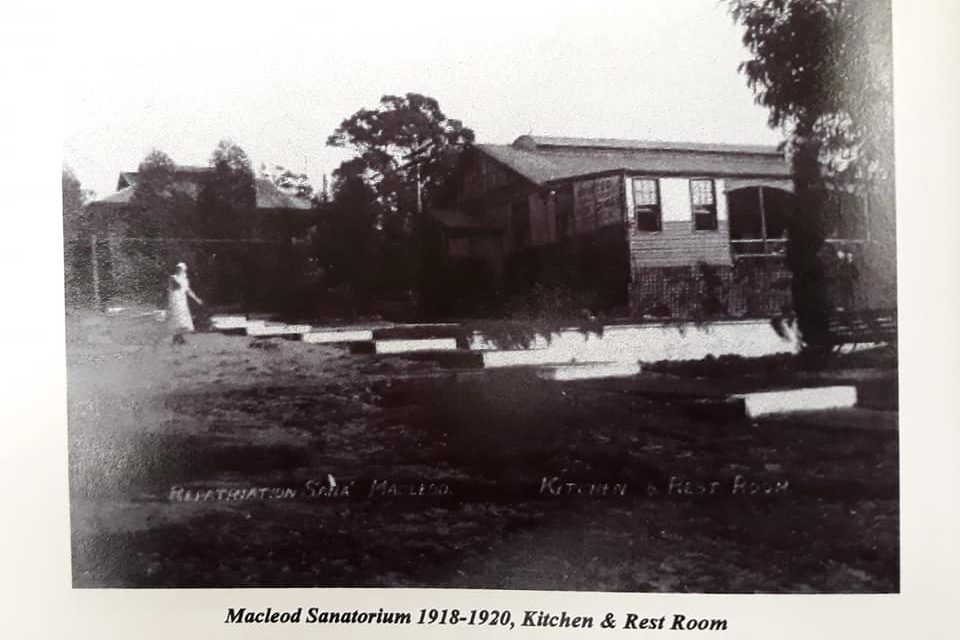

Until 1964 a goods train rail line came up into the Mont Park site from Macleod station and materials were brought up for constructing and refurbishing the wards. Also coal for power plants and other supplies were transported on this rail link. The Macleod Wards were not substantial buildings in the early days. They were mainly long, low white and brown wooden glassed-in bungalows, sometimes referred to as ‘chalets’ because of their open, airy configuration.

Life at Macleod Sanatorium early in the twentieth century

Although one report in May 1918 in the ‘Melbourne Age’ presented the Macleod Sanatorium in a very poor light, with bad food, and lack of clean bedding and clothing see https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/155098761, another report in November 1918 from the resident Chaplains was much more positive, see https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/154258427?#

In 1920 Britain’s Prince of Wales paid an unofficial visit to Macleod Sanatorium which was an entertaining departure from the routine. Newspapers described the scene rather whimsically as where: ‘airy wards look out towards the east over green fields, with, away in the distance, a line of ranges showing up on the horizon’ https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/203710836/18778160#

In 1921 the Repatriation Department took over administration of the Macleod Sanatorium from the Defence Department.

By 1922 the Red Cross Society had raised funds to have a croquet lawn installed for the veterans https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/140787373?# as well as installing a veranda to cover the porches. A tennis court, gym equipment, a laundry and reading and music facilities also resulted from fund raising efforts. Local groups from Greensborough, Eltham and Hurstbridge provided weekly afternoon teas with cakes, and flowers to decorate the tables for the men. Distinguished guests such as the Governor and Melbourne Mayors often visited according to the newspapers of the day, and the wards were then decorated with bunting and flowers.

So although being in a Sanatorium sounds very grim, there was respect and compassion shown for the veterans and efforts made to ameliorate their circumstances.

The long wards all ran north-south on the Gresswell Hill, stepped down along the quite steep eastern slopes, and had quite pleasant views. Levelled out areas near the base of the hill were utilised as a tennis court and croquet lawn.

Men were encouraged to play a variety of sports and worked on the surrounding land producing copious vegetables and tending poultry. Other work therapy for the purpose of retraining the men, involved leather work, wood work, building construction and concreting.

Springthorpe Estate Development after closure of the Hospitals

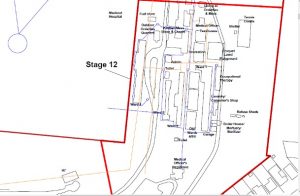

Maps from the Environmental Assessment Reports (2003) for the re-development of the area into Springthorpe Estate, show the considerable number of building which comprised Macleod Sanatorium before it was dismantled. These buildings included four wards, a boiler house, carpenter’s shop, occupational therapy workshops, administration, kitchens, recreation rooms, female quarters, male quarters, the Medical Officer’s residence and gardener’s sheds, as well as a croquet lawn, tennis court and a children’s playground.

In the 1940s there had been substantial building work, and ultimately the Macleod Hospital was productively re-purposed in 1960. From a Sanatorium it became the Macleod Repatriation Hospital, and at about the same time, Gresswell Hospital became a public Drug and Alcohol Rehabilitation Centre. TB was no longer a widespread and debilitating problem because drug treatment and vaccination had become available, and the facilities could be revamped. By the 1980s Macleod was known as a Veterans’ Affairs Aged Care Facility, with occupational therapy, physiotherapy and social work services for the veterans and some of their widows.

Interestingly, aerial photographs show a substantial amount of tree growth on the Macleod and Gresswell sites between 1945 and 1954. Gresswell Hill (with its water tank, designed by Sir John Monash in 1912) now became more densely treed, whereas it had been quite bare of trees and shrubs.

In 1993 Macleod was closed and the whole Mont Park site was developed for housing as the Springthorpe Estate.

Fortunately much vegetation still exists in the spacious public areas of Gresswell Hill and the Gresswell Reserve. Some very old river red gums and pine trees planted 100 years ago remain, and kangaroos thrive in the surrounding popular bushy Reserves, see https://www.montparktospringthorpe.com/flora-fauna/

Article contributed by Kathy Andrewartha (May 2020), with thanks to Mr Arnold Wheeler.

Resources:

‘Special Hospital for Soldiers’, The Age (Melbourne) 1 June 1916 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/155086241

‘Treatment of Soldier Patients’ The Age (Melbourne) 18 May 1918 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/155098761

‘A Visit to Mont Park’ Spectator and Methodist Chronicle 20 November 1918 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/154258427?#

‘Macleod Sanatorium’ The Australasian, 28 October 1922 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/140787373

‘Prince Surprises Diggers. Informal call at Sanatoria. Tuberculosis patients delighted’ The Age, Melbourne, 12 June 1920 See https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/203710836/18778160#

GHD Pty Ltd Report for Urban Pacific Ltd, 2003 – Environmental Assessment Reports

Janine Rizzetti (2020) One Hundred Years Ago: May – June 1920. The Heidelberg Historian, June (318), pp. 8 – 10.

Le Get, Rebecca, 2018. “More than just ‘peaceful and picturesque’: how tuberculosis control measures have preserved ecologically significant land in Melbourne”. Victorian Historical Journal, vol. 89 (1), pp. 67 – 87